BEFORE DONALD TRUMP became president of the United States, before COVID-19, before Michael Waldren says he continually worried about “the inevitable collapse of the world,” bedtime was actually soothing.

Back then, Waldren, who lives in Long Beach, California, could go to bed later in the evening, assured that he was going to sleep through the night. Back then, he didn’t have to drink wine or beer or take sleeping supplements to calm his mind.

“Now my days are non stop. From the moment I wake up to the moment I fall asleep, there is no room for me,” says Waldren, who is 39. “Falling into bed is about embracing the only portion of the day that I own.”

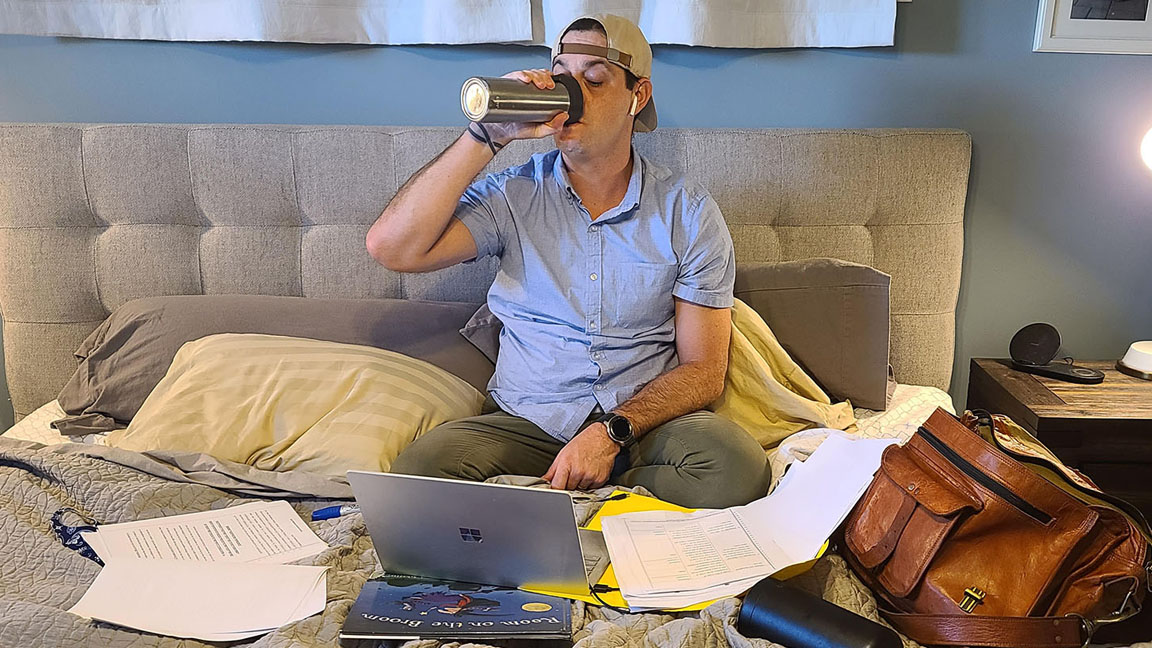

Waldren is a Los Angeles attorney who represents low-income domestic violence victims. His wife is an emergency-room doctor. Because of the pandemic, the couple is homeschooling their two children, ages 4 and 7, and Waldren is working mostly from home, where the family has put him in charge of cooking, laundry, and bedtime stories.

Sometimes, by his own bedtime, Waldren is so tired he can’t muster the strength to brush his teeth. On those days, he says: “I rinse my mouth out with mouthwash and collapse into bed.”

At first, sleep comes hard and fast. But it generally lasts only 3 to 4 hours. After that, Waldren says, the rest of the night belongs to the part of his mind that insists on preparing for the next day’s challenging case or the anticipation of a difficult opposing counsel.

The stakes are high, especially right now in the midst of the pandemic, as this is a time when domestic violence victims have fewer resources than ever. Domestic violence shelters are receiving less funding in tight financial times, and homelessness is increasing.

Desperate client calls and texts come through at all times of the night. Sometimes prosecutors won’t prosecute the abusers because they don’t want to send perpetrators to the Men’s Central Jail—where the odds of contracting COVID-19 are extremely high.

“I stew and I fester,” Waldren says. “And I ask myself: ‘Dear God, when will it ever end?’”

Perhaps the most surreal part of his life is working around his children at home, where he sequesters himself in a corner office away from them, so as not to expose them to the trauma inherent in his career. “But it still happens,” he says. “I will be reading a declaration about a child’s biological father abusing him/her and my own child will be tugging at my pants leg, trying to show me a drawing.”

When he awakens after those first three or four hours of sleep—somewhere around 2 a.m.—Waldren says he often ends up scrolling through his phone for the latest bad news. On Monday he read an article in the New York Times headlined: California Republican Party Admits it Placed Misleading Ballot Boxes Around State. That was enough “tangential trauma” to keep him up for the rest of the morning, Waldren says.

Coffee kept him awake the rest of the day, for a while. But then, he says, it did what it does at such high and continual doses: it “over caffeinated me and gassed me out” and kept him from sleeping more than a couple of hours a day for four or five days straight.

Waldren’s bedtime is at 9 or 9:30 p.m. But his children wake up at the non-negotiable time of 6 a.m. Then, he says, he thinks the same thought he always seems to think these days: “I don’t know how much worse it can get. But every day, we get some form of new worse.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.