FOR DECADES, Salt Lake City psychologist Mike Sheffield has had a complicated relationship with sleep.

“It’s hard for me to turn off my mind,” he said. “I struggle to slow my mind down.”

It started with chronic fatigue syndrome nearly 25 years ago. When that condition improved, the sleeplessness nevertheless came back with a cancer diagnosis in 2010 and lasted through two years of worry about whether he was going to live or die, Sheffield said. Even when his long-term survival became more evident, Sheffield, now 56, said nights of uninterrupted sleep have not become a regular reality again.

No matter what he focuses on—his home remodeling project gone awry, or the state of this country’s politics— “I have a hard time sleeping through the night,” Sheffield said.

He struggles with the decision to take sleep medication, going through times when he takes it and periods when he doesn’t. Complicating the situation is the fact that Sheffield was diagnosed with sleep apnea several years ago, and so breathes with the help of a CPAP machine.

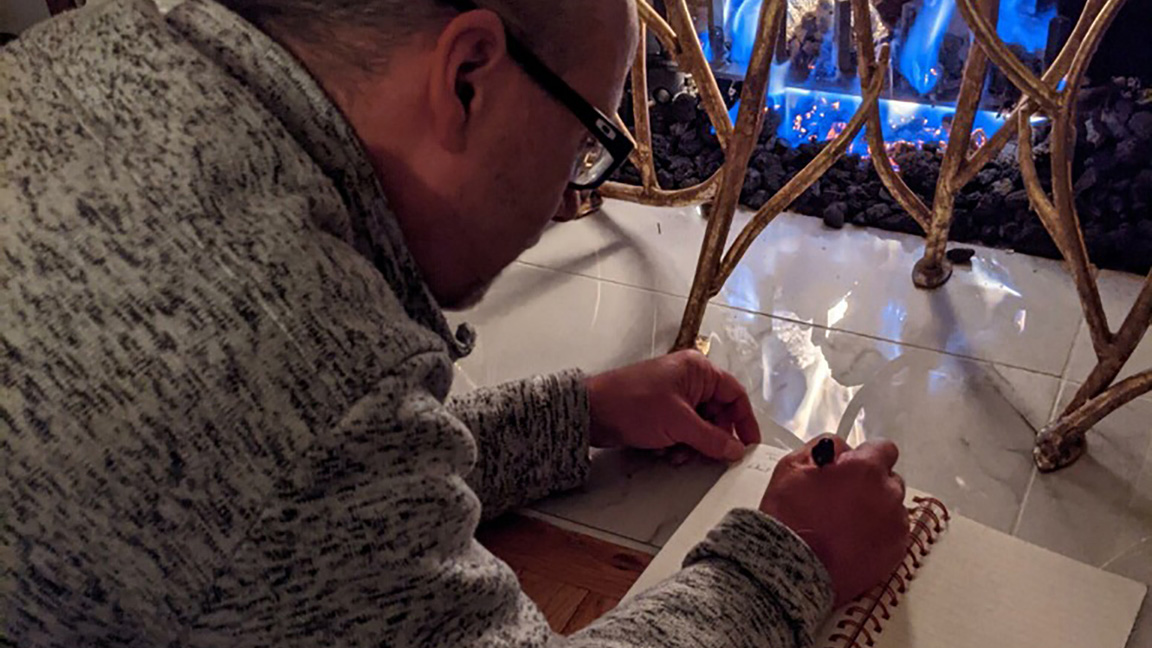

Yet there is always something Sheffield looks forward to each night: the meaning and sometimes even guidance that he’s learned to garner from his dreams. Thus, a red notebook remains on the nightstand by his bed. When the dreams do come, Sheffield wants to be ready to jot down the details and ponder them later on.

“I have made major decisions in my life because of my dreams,” he told me.

Countless dreams have proved to be extremely useful in his daily existence and personal growth, he says. In fact, two of them forever changed his life, he says.

The first one came in 2005, when Sheffield said that he was wanting to leave his full-time job to work on his own, but did not feel he had the financial means to make that leap.

“I am staying at a condo complex,” he said—when he talks about these dreams, no matter how much time has elapsed, he still uses the present tense—”and I follow this guy to a cliff overlooking the water where there are huge waves crashing across the rocks. It’s called ‘The Tides of Ruin’ and the guy—without hesitation—dives in.

“I knew it meant certain death. But I was connected with him and I have to follow. So he dives in and once I’m in the water too, he just disappears. I’m just by myself, swimming deep under the water.

“I know if I stay deep, I’ll be OK. And I know if I get to the surface, I’ll be smashed and die. So I’m swimming and I see a serpent below me, and right as I reach the shore, the serpent burns up completely and the bones fall to the ocean floor and I die at the same time, just as I’m reaching the shore.”

Suddenly the scene changed: he was back in his condo with his friends, and the man who jumped in the water—Sheffield has since dubbed him The Leaper—walked in. This time, the Leaper’s heart was visible inside his body.

“When I woke up, my first thought was: ‘I have to take the leap, even though it feels like I will be ruined,” Sheffield said. “I know I’m going to have to swim deep and not near the surface, where I would be completely battered by fear and turbulence.”

Concluding that the characters had represented parts of himself, Sheffield decided to take the dive. He took out a substantial home equity loan. He started doing psychological testing on his own. He also immersed himself in writing songs, poetry, and autobiography. And he tried to start a business offering personal workshops in the wilderness.

“And for various reasons, none of those things panned out,” Sheffield said. Yet the entire time all that was happening—even when he thought his financial situation might force him to sell his home—Sheffield remembered that dream, reassuring himself that he was traveling through a deep, albeit inscrutable process.

“I believe that dreams can give access to the steps of the psyche, as well as all the energy of the psyche, and so you can experience all of who you are in dreams,” Sheffield said.”You can open up to something deeper that wants to come through.”

Back in reality, the woman with whom he was having a relationship offered to rent Sheffield’s home. Intending to eventually live in his truck, Sheffield accepted her proposition and moved—temporarily, he thought—into a room into the basement of the house. Six weeks later, he was diagnosed with breast cancer.

His then-girlfriend vowed to remain by his side and Sheffield found himself navigating a terrifying terrain upon which he needed to decide whether to have a single or double mastectomy. The oncologist he was working with at the time said that when it came to situations like Sheffield’s, particularly those involving men, the suggestion was generally to remove only one breast.

Still uncertain as to what to do, Sheffield had another dream: “I meet these two girls and somehow I know that one has one breast and the other has zero breasts…We’re all going to this parade and the one with one breast kind of wanders off, talking to other people. And the one with no breasts stays close by me and keeps talking to me and we are developing more and more of a connection in the dream.”

With a profound feeling of peace, Sheffield went ahead with the double mastectomy.

Though the terror of a cancer recurrence stole many nights’ sleep, the psychologist’s relationship with his dreams, and thus with himself, saw him through the fear. As he had with the dream about The Leaper, he said, he referred to the notes about the dream in the journal to help him.

“I got panicked every day for two years,” Sheffield said. “Sometimes it would last for 10 minutes and sometimes it would rage for hours. And I just, I just kept going.”

It turns out that Sheffield never left that house he thought he would have to sell. He and his wife —the same woman who rented his home and saw him through the cancer—still live there. Even the clarity to marry her made itself evident in a dream, Sheffield said. His finances have improved dramatically since then. And in hindsight, he can see how things worked out for him while he followed his commitment to “dive deep” into uncertain waters, he said. Doing all that inner work changed him, preparing him in unexpected ways to navigate what was to come.

Of course new dreams continue to come. But sometimes, because of his inability to sleep, Sheffield is hesitant to focus on writing them down. He worries that the writing will more fully wake him up, and cause him to lose precious sleep.

Still, he wills himself to push through the jostled nights of fitful sleep to use the red notebook. Without that effort, he knows, the memories of his dreams will fade away unnoticed.

“I have this commitment to try to make something beautiful out of what happens to me,” Sheffield said. “And dreams help me do that.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.