MORE OFTEN THAN not, the exhaustion that Sylvester Miller feels when he tries to fall asleep after work is so layered, so deep and so visceral, that the pain of it keeps him awake.

“I have to pop pain pills before I go to work, and also sometimes after,” Miller says.

Sure, the pills eventually help Miller fall asleep—usually around midnight or 1 a.m., But they also keep him groggy when he wakes up in time to go to work—around 3:30 a.m.

And since Miller, 51, works seven days a week—40 hours Monday through Friday hauling 50 to 60 pound planks of wood at a manufacturing plant and then 16 hours Saturday through Sunday as a security guard—the cycle of exhaustion never ends.

“I have to be physically on top of my game in one job and mentally aware in the other,” Miller says. “On Mondays and Tuesdays I am dragging. And then when I try to get to sleep, my mind is racing.”

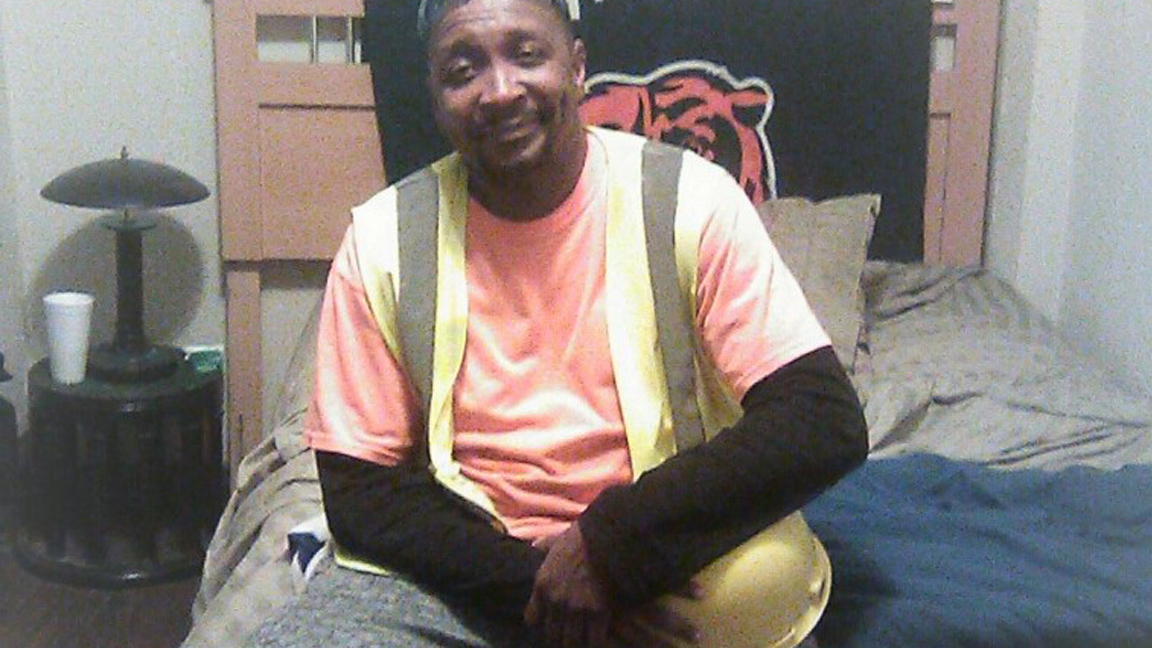

It is 4 p.m. on a Tuesday. Still in his work clothes, Miller sits on the edge of his bed to talk. I can hear the tiredness in his voice, a gravity that slows his words down and makes them sound creaky, like a rusty hinge. “I’m so tired,” he says. “Lord knows, I’m exhausted.”

Just five months ago, Miller emerged from an eight-and-a-half-year period of homelessness. Before that, he spent a decade in and out of jail and prison for dealing drugs, he says. Now, though, he says his life “has taken a 180.”

“Everything is about work,” he says. “I need to pay my bills and be responsible. And coming out of homelessness—well, there are a lot of things that I have never done before.”

This is the first time in his life that he has paid rent, he says. He lives on the far West Side of Chicago, in a narrow three-bedroom, one-bath apartment that he shares with two other men who work. Not so long ago, Miller lived with his girlfriend, the mother of his two now-adult children. She paid all the bills, Miller says. He talks about that time with surprising transparency.

“She had her own place. I didn’t,” he says. “I moved in with her and we ended up having two kids together. I was still a hustler. She was responsible for the bills and everything. I never took the time out to do any of that. I just did what I wanted to do and she moved on.”

Now Miller is single—a state he hasn’t experienced in so long that it feels like another first.

“We broke up almost two years ago,” he said. “That relationship just meant so much to me. I feel guilt-ridden because I think I let my family down.”

The loss is also part of the pain that keeps Miller up at night.

“I’m used to sleeping next to her. I’m used to being around my family. This is a new world for me. Even though I work a lot, I’m at a lonely place.”

Letting go of old friends has been a necessary part of his recovery, Miller says. So has the support of good-hearted church folks who made sure he had clothes and food, as well as friends and family members who allowed him time on their couches. Yet many relationships have grown strained, as Miller says he knows that if he kept them, he would likely end up in the life he has worked so hard to leave behind.

Making new friends has been more difficult than he anticipated: “There are some good men at work. But we talk and then we go home.”

His own family is spread out across the country, he says. And besides, they have never been particularly close.

“Everyone claims to be so busy,” he says.

His manufacturing job pays $13 an hour and his security job pays $14 an hour, says Miller, who blames his lack of education—he never graduated from high school—for his low wages. He knows he could go online and work toward his diploma. But the draw to make more money is too strong to stop and do that.

“I want to buy a house and life insurance in case I die, so that I can leave my family money,” he says.

Recently, lab results showed blood in his urine, Miller says.

“God helped me beat prostate cancer four or five years ago,” he says. “Now I am worried the blood that showed up in the scan means that the cancer is back. I try not to think about it.”

Thoughts of death are also part of the pain coursing through him at night, he says.

“I have to believe there is a God,” he says. “I know there is a God. I beat homelessness and prostate cancer. I know my health and strength come from God.”

When he can’t sleep, he gets up at night and plays his “old dusties”—classics from Earth, Wind & Fire or Marvin Gaye. Or he gets up and walks around his room. Or watches a movie on his phone. The next morning he feels as if he has been in a fight, he says, his eyes are so red and swollen.

Still, it is as if he can’t work enough. This week Miller plans to start a third job working four or five hours on weeknights for a cleaning business. It pays $460 a week—enough to allow him to start saving a decent amount of money.

“Everything is about work,” he says. “I got to keep it all moving.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.