Dems Spent Half of 2021 Blocked by Filibusters of Voting Rights Bills

The current Senate rules regarding legislative filibusters, in place since 1975, are seen by some lawmakers as immovable—except when they might crash the global economy, when they aren’t. Last week, 14 Republican senators joined every Democrat in a creative arrangement to temporarily increase the federal debt limit by a majority vote, preventing a potential self-inflicted economic catastrophe that would come with debt default.

When it comes to considering major legislation that protects access to elections, though, such breakthroughs have been far harder to achieve, even just among Democratic senators. Currently, it takes 60 Senate votes to advance a legislative item over an objection from a single senator, and conservative Democrats Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema have been the lone holdouts in changing parliamentary rules to be able to hold votes on bills if a majority so moves.

There are a number of possible fixes to Senate rules that might reduce its obstructive power—requiring a “talking filibuster” as depicted in popular culture, for example—if both Manchin and Sinema would agree to go along with their colleagues, or create a filibuster “carve-out” for the consideration of voting rights bills. A handful of other Senate Democrats, including Jack Reed of Rhode Island and Mark Warner of Virginia, have expressed skepticism of changing the filibuster, and there’s been chatter that some Democrats are pleased to let Manchin and Sinema be the faces of opposition to filibuster reform in the media.

In the past decade, these arcane Senate rules have been changed twice through the so-called “nuclear option,” both times in the face of filibusters of nominees by the opposing party: in 2013, then-Majority Leader Harry Reid changed the process for advancing all executive branch nominees and judges besides Supreme Court judges; and in 2017, then-Majority Leader Mitch McConnell changed it for Supreme Court nominees. Also called “reform by ruling,” the nuclear option is weighty in creating a new precedent by a senator raising a point of order, or claiming that a Senate rule is being violated, and the presiding officer agreeing, or being reversed by a majority of senators.

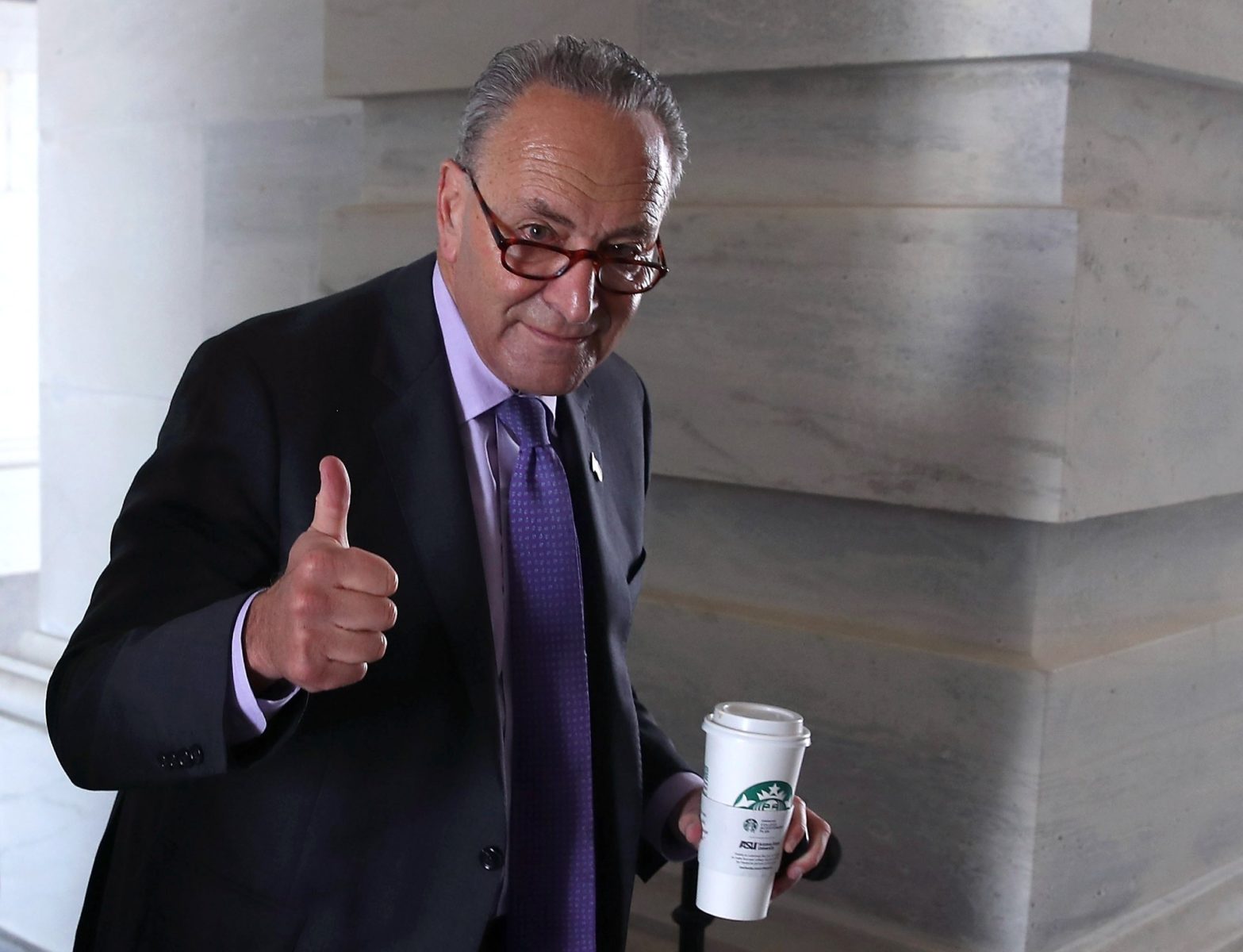

The anti-corruption group RepresentUs, which campaigns for democracy reforms, says that this year, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.)’s approach has been similar to Reid’s, and presents an entire universe of difference from McConnell’s. Reid faced GOP obstruction on approving Obama’s nominees in the 112th Congress, and in the 113th Congress that started in 2013, and it wasn’t until late November that year that he finally changed the rules for high-level nominees—261 calendar days after the first filibuster of a nominee the year.

McConnell, on the other hand, changed Senate rules in about one hour in April 2017 after Democrats attempted to filibuster Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch.

Schumer now stands at about 170 days since the first of several Republican filibusters this year of three major election reform bills: the For the People Act, passed by the House in early March; the compromise Freedom to Vote Act, designed by Manchin but blocked in October; and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would restore some protections of the landmark Voting Rights Act, but was blocked on Nov. 3 from debate.

“We’re heartened to see that conversations are happening about ways to allow the Senate to legislate again in the face of years of intransigence; we’ve also seen tons of blocks prior to this year,” Damon Effingham, director of federal reform at RepresentUs, said. “Especially on an issue as important as voting rights, which are under attack in this country, finding a path to legislate here, on an issue a majority of Americans agree with and that the majority in the Senate supports, is really important.”

States with conservative governments have passed dozens of restrictive voting measures this year, with hundreds more restrictive bills that could be carried over into next year’s legislative sessions, according to Voting Rights Lab. In many battleground states like Georgia and Wisconsin, pro-Republican gerrymandered maps have already been established and could stand for at least a decade without federal intervention.

“What’s happened over the past year has been important to show the willingness of the Democratic majority to engage on this issue and not railroad anyone— they went through the For the People Act, and a process of accepting amendments in committee, but hit a brick wall,” said Effingham. “They brought it to the floor as just Democrats and were unable to advance it there. Lots of actions have been taken to make sure this isn’t roughshod running over the minority, but instead engaging the minority in this process.”

At a CNN town hall in early October, Biden expressed willingness to support changing the filibuster rules, but made clear that he believed pushing too hard on the issue of voting rights would endanger the passage of the Build Back Better Act.

One week ago, a group of young people and students in Arizona launched a hunger strike to compel Senate Democrats to prioritize a plan that passes the For the People Act this year, ensuring greater election protections. After a virtual meeting on Dec. 9 with key vote Sen. Sinema, who told the activists that she supported voting rights bills but would not commit to a position on loosening filibuster rules, the hunger strikers, coordinated by the nonpartisan group Un-PAC, moved their protest to D.C., to highlight the need for White House action. In a statement, the group named the president as the next mover: “We still have not received a response from the Biden Administration regarding our request to meet with President Biden to discuss the moral urgency of this moment, and the need to pass the Freedom To Vote Act this year.”

RepresentUs’ Effingham said, “We would like to see Biden be more present in this debate, because at the end of the day, passing anything without protecting our democracy leaves any other issue or priority in danger.”

For more on reform campaigns for democracy in the U.S. Senate, get the free Sludge newsletter.