Over the past few years, large companies have come under pressure from activists to reckon with their environmental impacts—for example, to disclose the climate footprint of their operations, or address the ways their industry groups lobby against climate policy.

Around 1,309 institutional investors and 58,000 individual investors have divested about $5.2 billion from fossil fuel industry assets, according to the Fossil Free campaign, a project of the nonprofit 350.org. Many investors have signed-on to a plan to reinvest in fossil-free funds aligned with principles like social equity and ecological well-being.

Financial institutions have in the past declared their support for climate action, as a group of big banks did just before the December 2015 Paris Agreement, only to continue to funnel investment to the fossil fuel industry. In the four years since the Paris Accord, from 2016 to 2019, nearly three dozen banks gave lending and underwriting totaling $2.7 trillion to the fossil fuel industry, according to a report last year by Rainforest Action Network and other environmental groups.

During that time, JP Morgan Chase was the world’s largest funder of fossil fuels, with over $268.5 billion in financing for companies profiting from extractive energy practices. Last year, activist shareholders called on Chase to disclose the emissions from its lending at its May general meeting, but their initiative fell just short of being approved, with a preliminary 48.6% support. Danielle Fugere, president of the corporate responsibility nonprofit As You Sow, said of the vote, “Shareholders today sent the message that it is past time for Chase to catch up with its peers, implement a strategy to decarbonize and de-risk its lending portfolio, and help build a more secure future for all.” Similar shareholder initiatives to act on climate were pursued in Europe and the U.S. at Chevron, ExxonMobil, Duke Energy, and Shell.

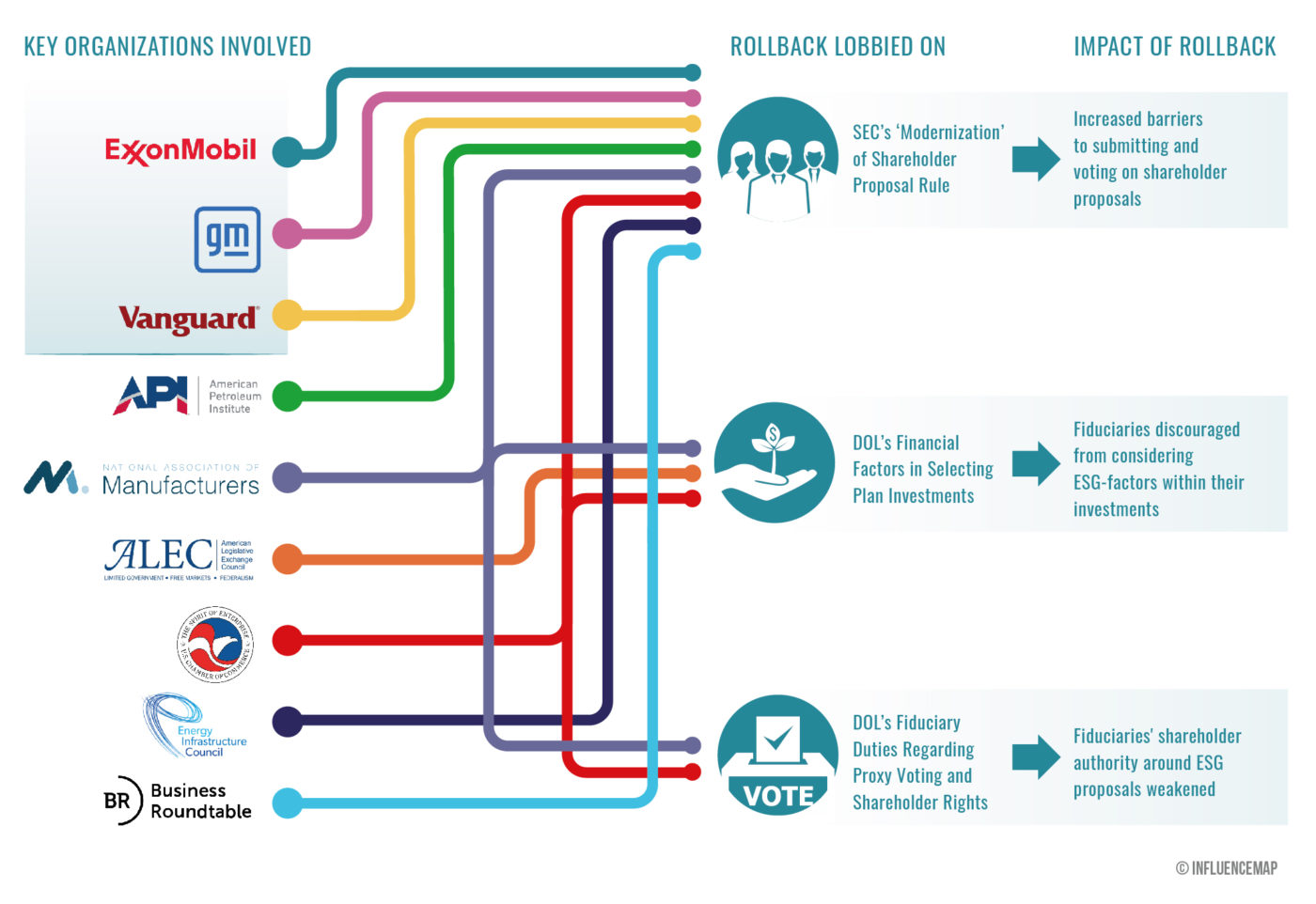

The U.K. charity InfluenceMap released a new report today on how corporate lobbyists supported the creation of rules in the final year of the Trump administration that make it more difficult for activists to submit shareholder resolutions. The report evaluates the lobbying activity for and against three federal rules that would curb efforts in ESG investing, a voluntary term that stands for the consideration of “environmental, social, and governance” factors.

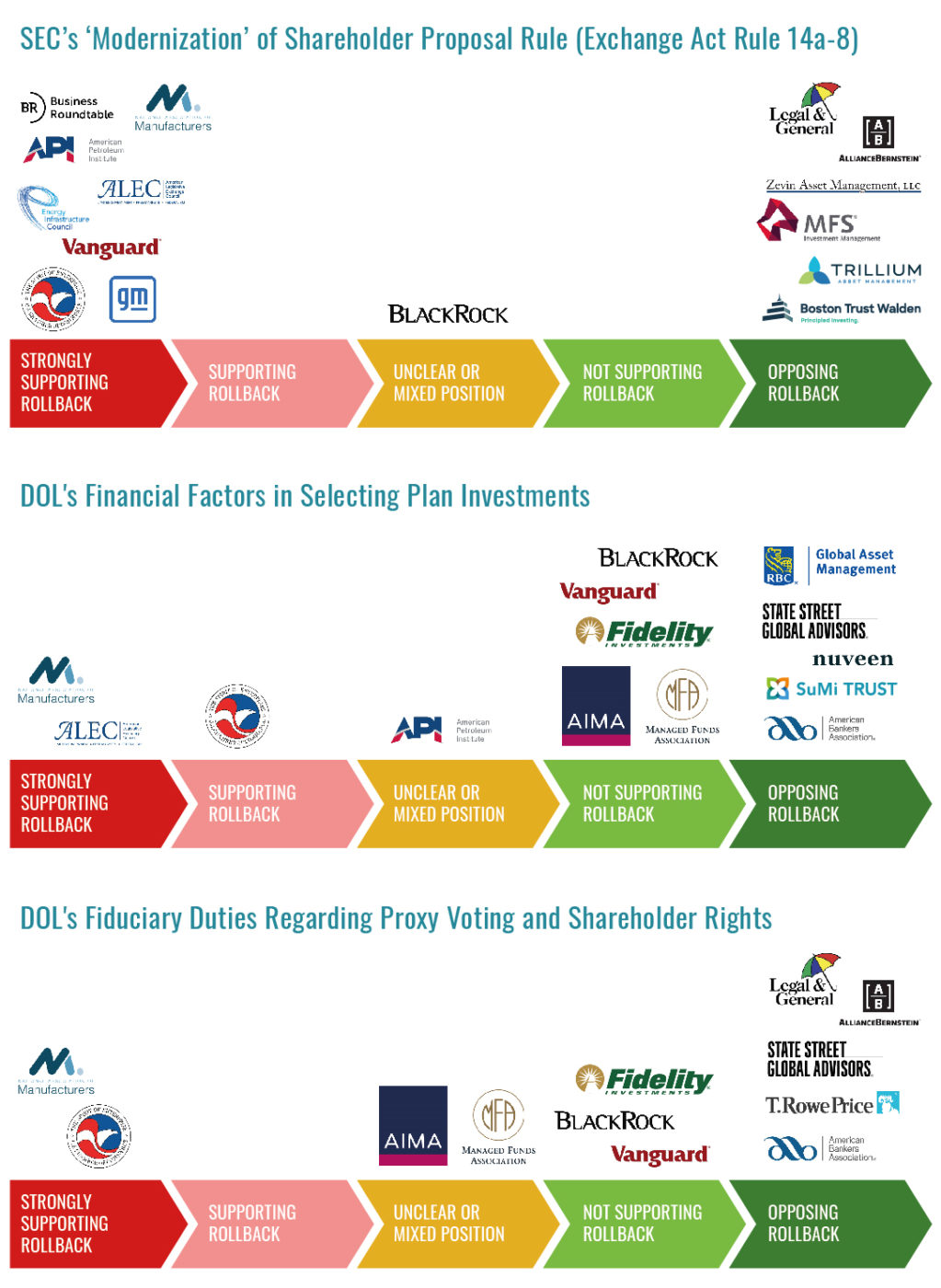

A rule change adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), called the Modernization of Shareholder Proposal Rule, increases the barriers for shareholders who want to submit proposals to be voted on at shareholders’ meetings. Two rules adopted by the Department of Labor limit the use of ESG investments in retirement plans and restrict fiduciaries’ ability to vote on ESG issues.

The fossil fuel industry and corporate trade associations that represent big businesses largely supported the Trump administration rules, while many smaller asset managers opposed the changes.

The day after Election Day, the SEC published its final Shareholder Proposal Rule, which significantly raises the requirements to enter a proposal for a vote, thereby making it harder for active investors to pursue ESG proposals. By reviewing corporate comments submitted in governmental regulatory consultation, InfluenceMap found that ExxonMobil and General Motors led the way in strongly supporting the SEC’s rollback of shareholder rights, which took effect on Jan. 4.

The SEC rule newly requires that shareholders must hold $25,000 in shares for at least a year, or $2,000 for at least three years, to submit a proposal, a sharp jump over the previous requirement of needing to hold $2,000 in shares for a year. Also, the SEC ramps up the threshold for resubmitting a previous proposal, now requiring 5% of support at first vote, 15% on a second vote, and 25% on a third vote. General Motors favored even higher resubmission thresholds, proposing moving the requirements up to 6%, 15%, and 30%.

Other corporate powerhouses that supported the Trump SEC rule included the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the major-company CEO association Business Roundtable, the Energy Infrastructure Council trade association, and the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), according to InfluenceMap’s analysis. The Business Roundtable’s 181 CEO members released a Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation in mid-2019 pledging “to promote an economy that serves all Americans” and protect the environment. The group, whose members include financial companies BlackRock, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley, said it endorsed the SEC’s changes to “facilitate the ability of corporate boards and management to drive long-term value,” and also suggested higher resubmission thresholds for proposals.

In its regulatory comment, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce wrote, “the shareholder proposal system has devolved into a mechanism that a small group of activists use to advance parochial agendas that are uncorrelated to enhancing the long-term value of public companies or their Main Street investors.” Investment giant Vanguard threw its support behind the rule, saying it was concerned about “the inclusion of proposals that have no realistic prospect of success and that may impose unnecessary costs.”

On the other side, many players in the asset management sector opposed the SEC rule, with BMO Global Asset Management stating that “the shareholder proposal process has made a positive impact on improving the ESG performance and corporate governance practices at U.S. companies, which in turn has led to us being invested in higher quality assets on behalf of our clients.” But BMO is itself a board member of the Chamber of Commerce.

In the two rules involving fiduciary duties that were finalized by the Department of Labor, carbon-intensive industry associations the U.S. Chamber and NAM again strongly favored the rollbacks. They were joined in support of one, a rule regarding the selection of retirement plan investments, by the corporate bill mill American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), according to the analysis. The shadowy, right-wing ALEC has received major funding from the Koch Brothers political network and works in secret with lawmakers to promote the use of fossil fuels. Regarding the rule’s requirement to pick investments solely on a financial basis, ALEC wrote, “the evidence from public pensions is that politically driven ESG investing leads to foregone gains and long-run volatility.”

The Biden administration and the new Democrat-controlled Congress now have options to remediate the three Trump changes, and one of the Department of Labor rules is already under review, suggesting it might be undone. The other two are likely candidates to be addressed—President Biden’s chairman-elect of the SEC, Gary Gensler, has developed a reputation as as a tough Wall St. watchdog, and some Democratic senators are advocating use of the Congressional Review Act (CRA), a 1996 law that allows Congress to expediently overrule recently finalized regulations by passing a joint resolution that cannot be filibustered beyond 10 hours by objecting senators.

The ambiguity around the ESG brand, which is a voluntary label that funds can simply choose to apply to themselves based on their own criteria, prompted John Stepek, the executive editor of financial news outlet MoneyWeek, to call it “greenwashing” earlier this month. Stepak noted that more than 2,500 existing funds in Europe simply rebranded as ESG, seemingly to hop on the bandwagon. The lack of regulation around the ESG standard opens up the risk that publicly-traded companies could outsource their polluting activities in order to remain in good standing.

Climate scientists laid down a marker that carbon emissions must be reduced 45% by 2030 in the landmark Oct. 2018 report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Toward that goal, divestment from fossil fuels is one of the strategies endorsed by environmental experts in the Exponential Roadmap, a package of 36 solutions across sectors designed to keep the planet’s warming within the bounds of the Paris Agreement.

Last month, two New York City pension funds took the first step in fulfilling a pledge they made last year, along with cities like London and Berlin, to pull their money out of polluting industries and put it into green energy. The funds, representing city teachers and other employees, voted to divest from $4 billion in fossil fuel company securities—a slice of the $240 billion in pension investments managed by the city, but a step hailed by climate campaigners in the group 350NYC. In December, the New York State pension fund pledged to cut off investment in oil and gas companies by 2025 and decarbonize its $226 billion in assets by 2040, a goal that state activists pursued for nearly a decade, and last May, the University of California completed a full divestment of its $126 billion portfolio from fossil fuel holdings.

The full report can be downloaded with a free account at InfluenceMap.

For more climate-focused coverage of the fossil fuel industry’s lobbying, sign up for Sludge’s newsletter.