NOTE: This department contains images and descriptions of carnivorous behavior.

THE HAWK WAS so close we almost didn’t see it. We were barely even into Central Park, at the near corner of the Sheep Meadow. I’d just swept my eyes over the open grass, thinking about how empty it was, when for some reason I carried my gaze around to my left and caught a glimpse of something immense and whitish in a tree. I’d taken another step or two, so that I was turning back over my shoulder, before I processed what I was looking at: it was so low in the tree, and so near to the path, and so evidently unbothered.

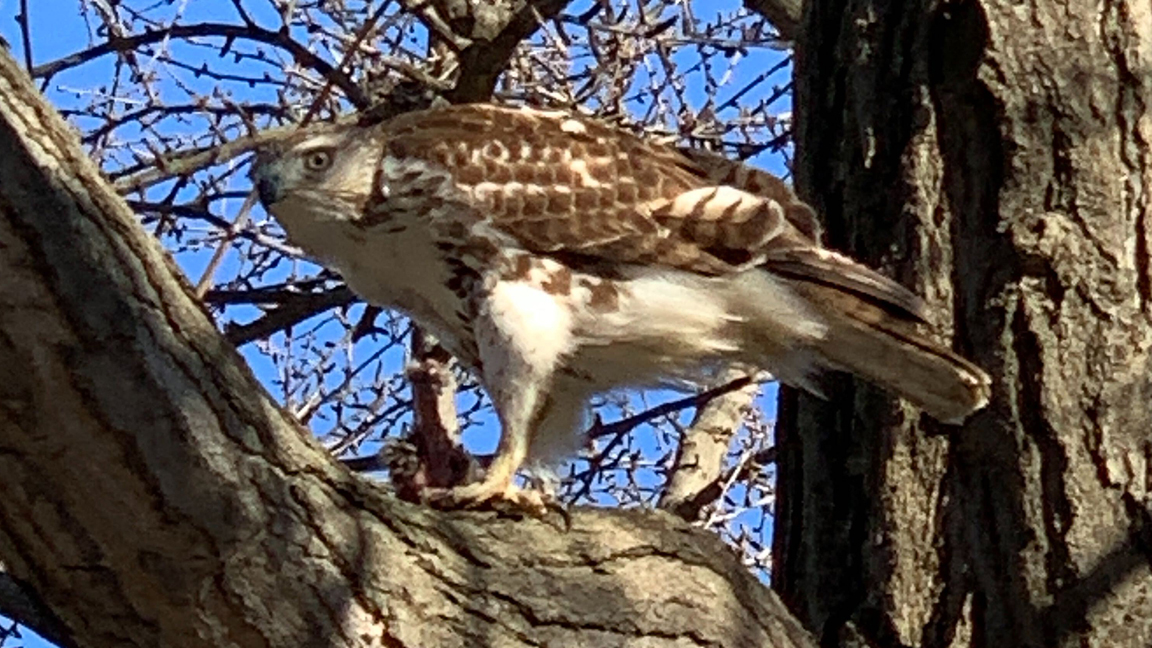

I called a halt and we doubled back. It was perched on a thick hump of a branch, right before the tree trunk. Even while we came closer, it still didn’t fly off, and as I tried to figure out why, we saw a squirrel’s tail hanging limp behind the branch. The hawk hunched over it, busy at work.

We circled a quarter-turn around the tree for a clearer angle. The hawk looked at us with a pale eye, then returned its attention to the meal at its feet. It had a sharp white eyebrow and, between that and its ruthless mien, I kept wanting to resolve it into a dashing, forest-hunting Cooper’s hawk. But the short thick tail and the plump white breast, with the familiar watch chain of brown streaks below, patiently insisted that here was a plain old everyday red-tailed hawk, too juvenile for its tail to even be red yet.

It was not every day that even a red-tail showed up like this, though. The branch was 12 or 15 feet up, and we were standing about 12 feet off, so the hypotenuse wasn’t even 20 feet. I tried to think of whether I’d ever been this close, for this long, to a live, free, uninjured hawk, with no glass in the way. I’d held trained ones before, an experience of awe in its own right, but those hawks weren’t exercising full discretion. The hawk tugged at the squirrel with its beak, stretching the dead tissue, tearing pieces off with a rubbery snapping sound.

Joggers and cyclists and strolling people kept going by. A few stopped and took pictures, but most didn’t notice what was going on. Here was nature audibly ripping meat apart, and there, a few yards off, was normal human business, flowing on at eye level. We’d nearly flowed past it, too.

The squirrel’s tail swung in time with the hawk’s exertions, but it had lost most of its volume. Whatever squirrel vitality had once made it fluff and bristle was gone with the brain stem down the hawk’s gullet. Had I seen this squirrel before, intact, among the other squirrels? One afternoon I’d tried to snap pictures of their long little bodies bounding over the grass of the meadow, with the lowering sunlight drawing them out all the more, but I couldn’t get the timing right.

The hawk defecated, throwing a rope of feces through the air. It splashed down not far from where we’d first been standing. Then the hawk bent back to its meal. A few years ago I read H Is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald—her memoir of training a fractious goshawk to hunt—with a sort of raptor-eyed fascination. At the age my children are now, I was more than semi-crazy for birds of prey myself; when I was in seventh or eighth grade, my mother had willingly taken me up what was then called the USF&G Building, the tallest building in Baltimore, so I could snap an endless stack of color slides of Scarlett, the resident peregrine falcon there, as she sat on her nest on the ledge outside an office window. Helen Macdonald had gone down a road I might, possessing a little more personal intensity, have ventured along too. She hadn’t mentioned, or quite possibly I hadn’t retained her having mentioned, how slow the eating process could be. One little scrap at a time! My children were interested enough in the hawk, but not devoutly so.

Then the hawk fumbled what was left of the squirrel and dropped it. The gray furry thing plopped at the base of the tree, flat in the dirt, its front parts missing and tail and hindquarters intact.

The hawk shuffled and turned around a little, tensing up and settling and tensing up again. It had lost command of the situation, and the equilibrium had been destroyed. People nearby were a matter of indifference when it held the meal in its own feet, but now it had to weigh the risks of trying to retrieve it.

We moved off a little, to give it a better chance. It stood where it was, undecided. If it had eaten its fill, presumably, it would have given up and left. It still wanted the squirrel. Another red-tail, this one in mature plumage, circled in the sun-filled sky nearby, then slowly receded eastward. One passing dog, a husky type, caught the smell of the carcass, and then another did, but their owners kept their leashes moving on a straight line even as their snouts turned toward the foot of the tree.

The volume of passersby thinned, then thickened again. The hawk could not convince itself to make a grab for it. We retreated further, but it stayed stuck on the branch. Finally we gave up and moved off, for the Wisteria Pergola, where we’d been headed in the first place. When we made it back to the corner, on the way home, the hawk was gone and the squirrel-half was still there.