Missouri Republican Blaine Luetkemeyer has a good thing going for himself. A partial owner in a St. Louis area bank that has nearly $200 million in assets under control, Luetkemeyer got a seat on the House Financial Services Committee shortly after being elected to Congress. The committee oversees banks like the one he partially owns. More recently, Luetkemeyer became the ranking member of the Subcommittee on Consumer Protection and Financial Institutions, which has jurisdiction over the financial regulatory agencies that regulate banks such as his, as well as the body of law pertaining to financial depository institutions.

If Republicans take over the House, Luetkemeyer would likely become the chair of the subcommittee, giving him immense power over both the laws governing his bank and the regulators that enforce those laws.

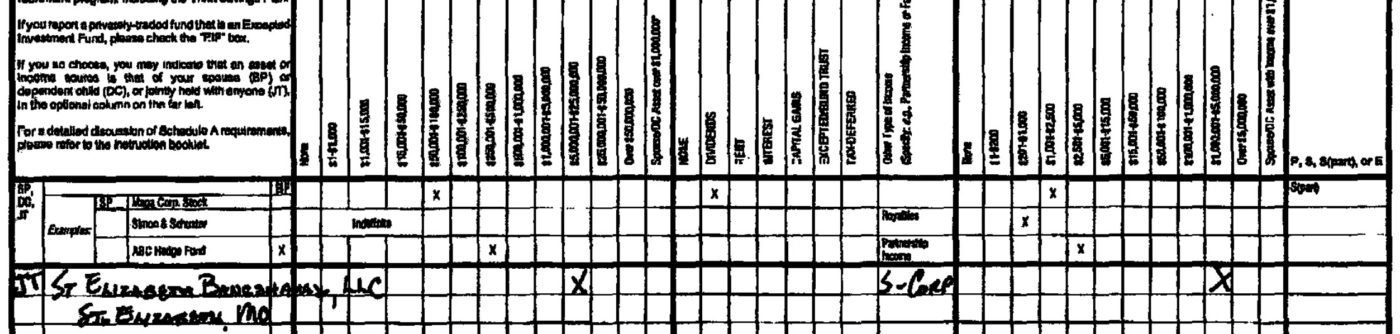

Luetkemeyer and his wife jointly earn between $1 million and $5 million annually from their stake in St. Elizabeth Bancshares, according to the representative’s annual financial disclosures. His wife is a member of the bank’s board of directors, and the bank’s president is currently his younger brother Brice, who was recently elected as chairman-elect of the Missouri Bankers Association lobbying group. Leutkemeyer indicated on his most recent annual filing that his stake in the company is worth as much as $25 million.

Not surprisingly, Luetkemeyer has been a friend to the banks since entering Congress. A 2019 scorecard from Americans for Financial Reform found that he voted in favor of all 38 deregulatory measures that received House floor votes in the 115th Congress. AFR characterized these votes as “measures to deregulate finance, and to, in some way, serve the interests of Wall Street and the financial industry at the expense of the public interest.” Furthermore, AFR found that Luetkemeyer voted in favor of every deregulatory measure that came before the Financial Services Committee that Congress.

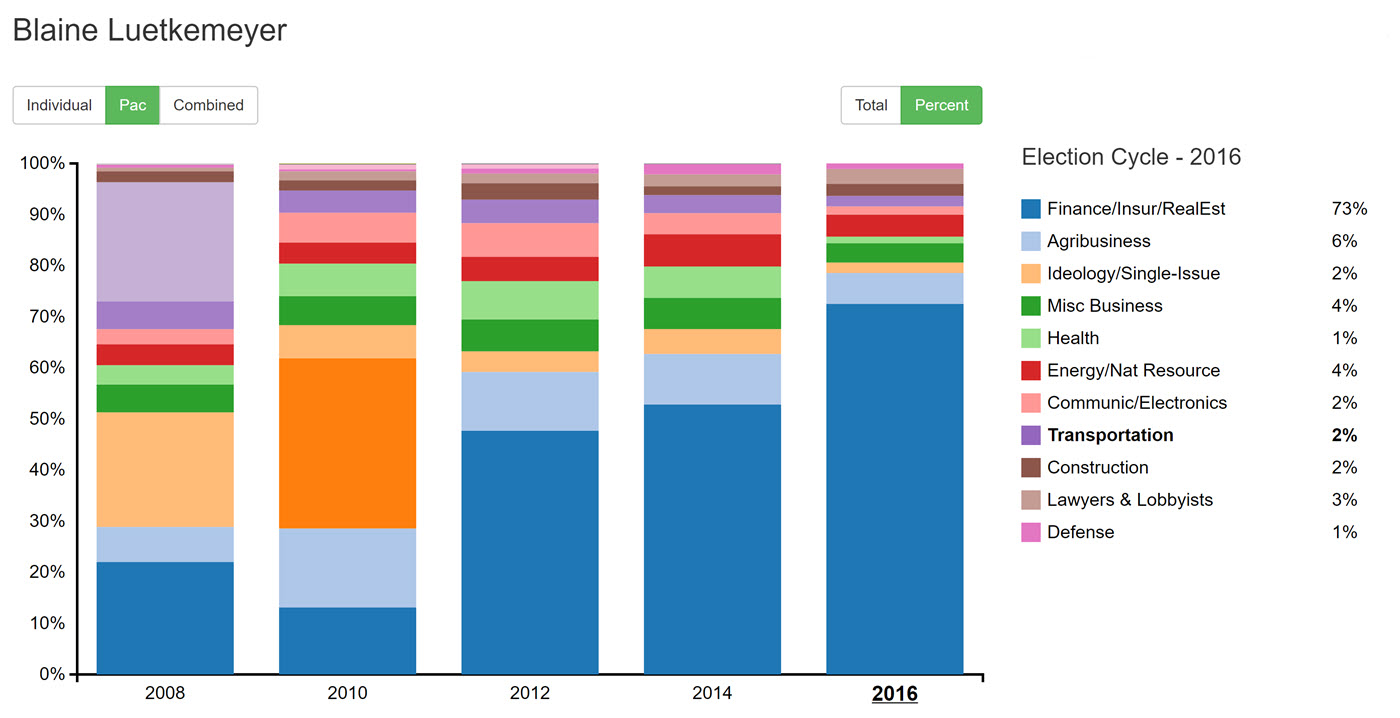

Wall Street has taken note of everything Leutkemeyer has been doing for them. The finance industry’s PAC donations to Blaine went up steadily during his first cycles as a rep, and by the 2016 cycle the sector accounted for 73% of his PAC donations. This information comes from the Explore Campaign Finance website, which does not have 2018 and 2020 cycle data:

In the 2016, 2018, and 2020 election cycles, Leutkemeyer got at least 70% of his campaign money from business PACs, mostly those affiliated with finance companies and banks, according to OpenSecrets. He is one of the most business PAC-reliant members of Congress.

He doesn’t really need the money for his re-elections. His district is R+18 and he hasn’t had a serious primary or general election challenge since joining the House. He does, however, need the money to hold onto his Financial Services seats that allow him to shape legislation impacting the bank he owns.

Financial Services is considered a “money committee,” and both parties require its members to pay a tax to sit on it. It’s not known how much the Republicans charge, but a leaked document published by The Intercept shows that Democrats charge $300,000 for a Financial Services subcommittee chairmanship like the one he holds. If he wanted to become the chair of the committee, his tax would likely double.

So, according to Bloomberg, Luetkemeyer got pretty mad when after he objected to certifying the electoral college results several financial industry PACs said they would be pausing donations to him and the 137 other GOP objectors in the House. Luetkemeyer “recently told donors that if corporations were going to put him on an enemies list, he would create a list of his own, said a person who attended the meeting,” Bloomberg reported. Luetkemeyer’s staff told Bloomberg that he couldn’t discuss details but that the representative did not call anyone an enemy.

The Popular Information newsletter listed some of Blaine’s past donors that said they would be pausing donations: “AllState ($9,500 to Luetkemeyer’s campaign), Amazon ($2,500), American Express ($10,000), AT&T ($10,000), Bayer ($5,000), Comcast ($7,000), Commerce Bank ($5,300), Exelon ($1,000), GE ($6,500), Hallmark ($5,000), KPMG ($10,000), Marriott ($2,500), Marsh & McLennon ($8,500), MassMutual ($10,000), Mastercard ($8,500), Morgan Stanley ($10,000), Nasdaq ($2,000), Nike ($1,000), PNC Bank ($10,000), PwC ($10,000), S&P Global ($5,000), and State Street ($6,000).” He also received donations from companies that said they would be stopping PAC donations altogether, Popular Information reported.

If these companies actually withhold donations, Luetkemeyer would have to dramatically change his fundraising to make sure he has enough money to hold the seats that let him oversee his own bank’s regulation. In the 2020 election cycle, he got just $16,287 from small individual donors, making up less than 1% of his total fundraising.

Luetkemeyer has proposed many bills that could benefit his bank and banking industry donors. His “Eliminating CECL Accounting Standard Act” would eliminate a new accounting standard for financial institutions called Current Expected Credit Losses (CECL) that will require them to account for all losses they expect from their loans, rather than only the losses that have actually been incurred. The American Bankers Association opposes CECL. His “Systemic Risk Designation Improvement Act” would change how banks are determined to pose systemic risks—and thus face increased regulation—from a size-based system to one based on an analysis of factors like an institution’s complexity and activities. Another bill he introduced, which passed the House in 2018, would tighten the conditions under which regulators can establish operational risk capital requirements for banks.